Introduction

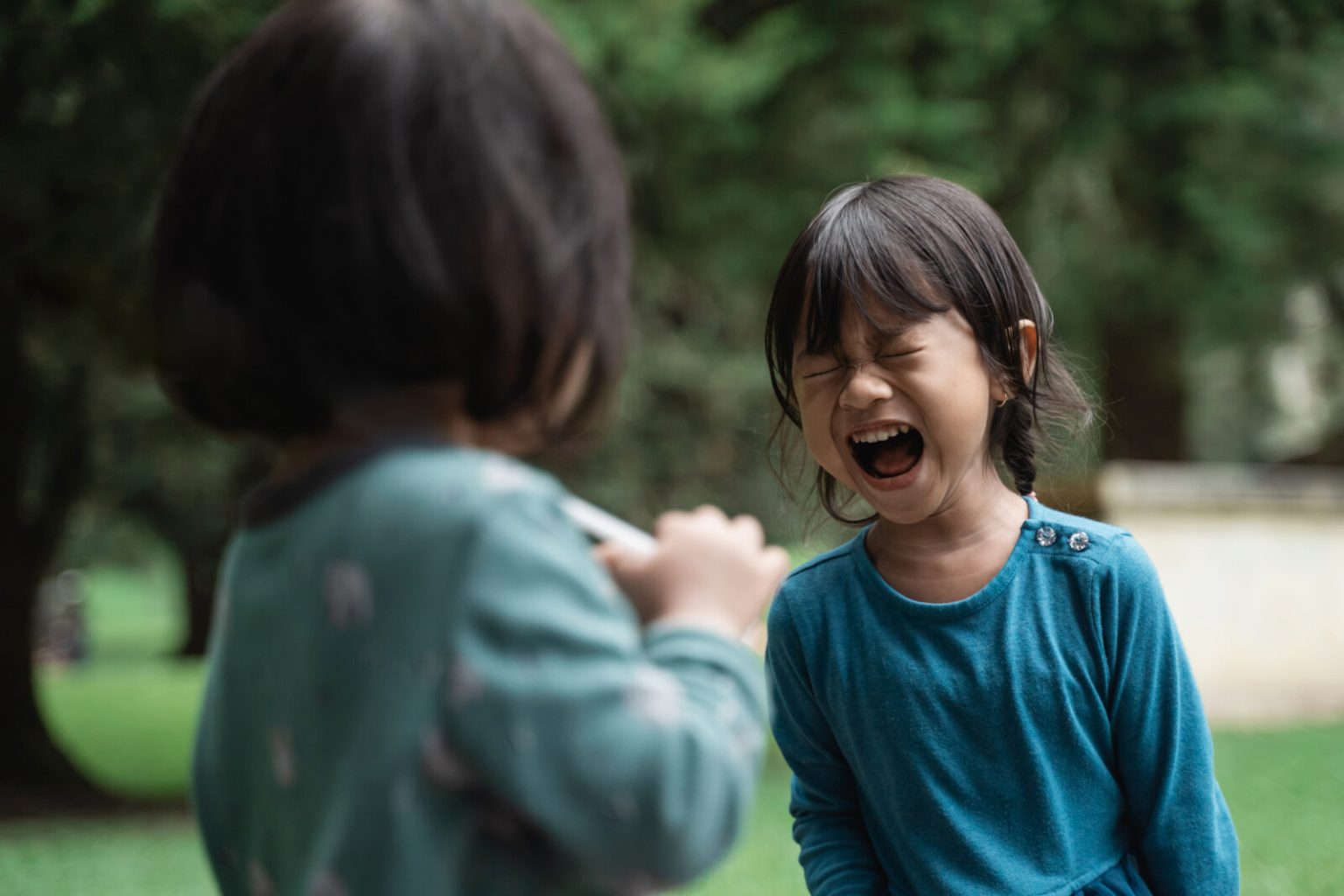

Every parent will, at some point, face an outburst of aggression from their child—whether it’s yelling, hitting, throwing things, or talking back. These moments can be frustrating, embarrassing, or even frightening. Often, they trigger strong emotional reactions in adults, prompting shouting, punishment, or withdrawal. But the key to helping children manage their aggression lies not in reacting harshly, but in responding with composed, purposeful communication.

What you say—and how you say it—when your child is aggressive can shape their emotional development, influence their behavior long-term, and strengthen (or weaken) your relationship. This paper explores what causes aggression in children, what to avoid saying in heated moments, and what phrases and strategies can calm conflict while teaching healthy coping skills.

Understanding the Roots of Aggression

Before deciding what to say, it’s essential to understand why children become aggressive in the first place. Aggression is rarely about defiance or manipulation—it’s often a signal of emotional distress.

Common Triggers:

- Frustration and helplessness (e.g., inability to complete a task)

- Unmet needs (e.g., hunger, overstimulation, lack of sleep)

- Emotional overload (e.g., jealousy, fear, anxiety)

- Developmental immaturity (young children lack impulse control)

- Modeling behavior (they’ve witnessed aggressive behavior from peers, media, or adults)

Recognizing aggression as a symptom—not the root problem—helps reframe your response from punishment to guidance.

What NOT to Say During Aggressive Episodes

When a child lashes out, it’s easy to react emotionally. But certain responses escalate rather than de-escalate the situation.

- “Stop it right now!” (in a harsh tone)

While you do need to set limits, shouting commands without empathy often increases tension. Your child may feel misunderstood, threatened, or ashamed.

- “You’re being bad!”

Labeling a child as “bad” undermines their self-esteem and doesn’t teach them how to handle big feelings. Focus on the behavior—not their identity.

- “Go to your room until you can act right.”

Isolation can be useful if it’s framed as time to cool off—but sending a child away in anger teaches them that strong emotions make them unworthy of connection.

- Sarcasm or threats

Statements like “Keep acting like that and see what happens” or “Why are you such a baby?” add fear and humiliation, making it harder for the child to self-regulate.

What to Say Instead: Constructive Phrases and Techniques

The goal is to help your child feel seen, safe, and supported—even as you correct harmful behavior. Here are strategies broken down by age and situation.

- For Toddlers and Preschoolers (Ages 2–5)

At this age, children don’t yet have the vocabulary or self-regulation skills to express complex emotions. Tantrums and hitting are often their only tools.

Say:

- “I see you’re really upset. I’m here to help.”

This validates their feelings and signals safety. - “It’s okay to be mad. It’s not okay to hit.”

Affirms emotion, sets boundary on action. - “Let’s use our words. Can you tell me what’s wrong?”

Promotes emotional literacy. - “I’m going to help you calm your body.”

Offer a calming hug or sit with them.

Strategy:

Use simple language, model calm breathing, and stay physically close if it’s safe. Avoid lecturing. Focus on co-regulation before any teaching moment.

- For School-Age Children (Ages 6–12)

By this stage, children begin to understand rules and consequences, but still struggle to control impulses, especially under stress.

Say:

- “You’re having a hard time. Let’s figure this out together.”

Signals partnership, not punishment. - “Can you show me with words what you’re feeling?”

Encourages emotional expression over aggression. - “You’re allowed to feel angry, but you’re not allowed to hurt.”

Reinforces boundaries. - “Take a break. We’ll talk when you feel calmer.”

Offers space for reflection, not rejection.

Strategy:

Once your child has calmed down, engage in reflective conversation: “What happened? What could you do next time?” Use this as a chance to build problem-solving skills.

- For Teens (Ages 13+)

Teen aggression often stems from social pressure, identity struggles, or feeling misunderstood. Teens are especially sensitive to tone and respect.

Say:

- “I’m not okay with how you’re speaking to me. Let’s pause.”

Sets boundaries while modeling self-control. - “It sounds like something deeper is going on. Do you want to talk?”

Opens the door to emotional connection. - “I respect your feelings, but we need to talk in a way that’s respectful too.”

Encourages mutual responsibility.

Strategy:

Avoid power struggles. Stay curious, not combative. Express your own feelings calmly. If needed, come back to the conversation later.

Core Communication Principles During Aggression

- Stay Calm to Regulate Their Calm

Your tone and body language matter more than your words. If you escalate, so will your child. Deep breaths, soft voice, and neutral posture help de-escalate.

- Acknowledge Feelings Before Fixing Behavior

Instead of jumping into discipline, start with empathy: “You’re angry because your sister took your toy. That makes sense.” Then move to problem-solving.

- Use “When-Then” or “If-Then” Statements

Instead of threats:

- “When your body is calm, then we can talk.”

- “If you throw the toy, it will go away until tomorrow.”

These connect behavior to consequences without shaming.

- Revisit the Situation Later

Once the child is calm, say:

- “What was going on for you earlier?”

- “How did that feel in your body?”

- “What do you want to do differently next time?”

Make repair part of the learning process.

Teaching Long-Term Coping Skills

While reactive moments are important, proactive teaching is just as crucial.

- Emotional Vocabulary

Help your child name their feelings: frustrated, overwhelmed, jealous, left out. The more specific they can be, the less likely they are to lash out.

- Calming Tools

Create a “calm corner” or toolbox with strategies like deep breathing, fidget toys, music, or drawing.

- Role-Playing Scenarios

Practice what to do in triggering situations: “If you feel angry when someone cuts in line, what could you do?”

- Modeling by Adults

Show your own regulation. Say out loud:

- “I’m really annoyed, so I’m going to take a breath before I respond.”

- “That made me mad. I need a minute to calm down.”

When to Seek Help

If your child’s aggression is frequent, severe, or impacting school or family life, professional support may be needed. Signs to watch for:

- Physical aggression that escalates or harms others

- Aggression combined with anxiety, depression, or withdrawal

- No improvement with structure or emotional coaching

Child therapists, counselors, or pediatricians can provide deeper assessments and tools tailored to your child’s needs.

Conclusion

Aggression in children is not a sign of bad parenting or a bad child—it’s a signal of emotional overload, unmet needs, or lagging skills. The words you use in those moments of intensity can either deepen the divide or build a bridge toward understanding and growth.

By approaching aggression with empathy, calm, and clarity, parents can turn outbursts into opportunities for emotional education. Over time, children internalize these responses, building the resilience and regulation they’ll need for a lifetime of healthy relationships.